Learning to Embrace My Heritage

By Meital Caplan

May 17, 2018

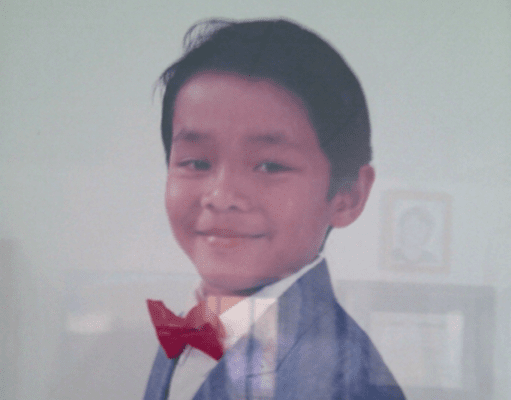

As we celebrate Asian American Pacific Islander Month, we are honored to share and elevate a personal reflection from Gold Chhim, our founding Director of Partnerships in the Bay Area of California, about how his Cambodian heritage influenced both his education and his career.

As a young man growing up on the East Side of Compton, California, I never quite understood my place in my community or society. I identified as an Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI), but rarely felt like my voice was valued in my school community or amongst my peers.

In middle and high school, my peers identified mostly as Latinx and/or African-American — I was one of a few AAPI students on campus, and we were all on our respective journeys to “fit in” with the general population, which, oftentimes, meant ignoring and discounting our own family stories and cultures.

During school potlucks, I would force my mom to take me to the local supermarket to buy “American food” instead of asking her to cook her “Chhim Famous Fried Chicken” because I feared my peers would view the Asian spices used in it as “too exotic” (I realize now that her fried chicken is, hands down, one of the best I will ever have).

I also resented my name because it wasn’t a “normal name,” and I was ashamed to share its origin, a story I now tell with pride.

My mom spoke almost no English when she arrived in America and didn’t know any American names when she was pregnant with me. When I was born, my mom asked the nurse “what’s something important?” to which the nurse replied “Gold.” My mom quickly followed by asking “How do I say I love it the most?” The nurse said: “It’s your main one.” So my mom named me Maingold.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but this mindset was extremely disrespectful to my parents and the journey they had gone through to grant their three children with educational and social opportunities that they themselves could never have dreamed of. My parents spent the majority of their lives in Cambodian villages living simple lives before being forced to abandon everything they knew because of the Cambodian genocide in the 1970s, where the Khmer Rouge government forced citizens into labor camps and murdered dissenters in an effort to change Cambodia into a Communist, agrarian-led country.

As a result, they were displaced and pushed to navigate inconceivable challenges on a daily basis — from hiding in jungles for days at a time, to not knowing when they (or their kids) would have another meal. Every few weeks, they moved under the darkness of night from refugee camp to refugee camp to avoid being captured.

Because of these horrific experiences, my mother worked to instill three values in all of her children. One was an unwavering belief in ourselves and our potential; no matter how difficult things were, we were more than capable and strong enough to succeed in spite of challenges. The second was a deep-rooted appreciation for the blessings we had; our family didn’t have much, but she didn’t let us take for granted the little we did have. Lastly, she ensured that we knew the value of education for achieving a better life. Despite her lack of formal education beyond the second grade, she had a deep-rooted “hustle” mentality and wanted each of her three children to have educational opportunities that she never knew existed.

I carried these values with me through my educational journey and had the privilege of attending my dream university: University of California, Los Angeles, better known as UCLA. Before setting foot on campus, I had convinced myself that college life would present amazing opportunities for me to grow and learn more about my AAPI identity; UCLA, after all, was one of the biggest and most diverse universities in the world. I would finally have the opportunity to meet and connect with other people “like me.” I quickly realized, however, that this was not the case.

The majority of my college peers grew up in affluent communities and didn’t understand the struggles of growing up in the inner city. As a first-generation college student born to immigrant parents, I had an extremely difficult time navigating the challenges of a major university. From completing financial aid forms to transitioning to on-campus housing; from understanding my still-forming identity to seeking support due to the increased rigor of college, everything felt foreign and intimidating.

After my first year, my GPA had fallen below a 2.0 and I was placed on “Academic Probation, Subject to Dismissal.” Simply put, I would be expelled unless I dramatically increased my academic performance. In my university-mandated meeting with my college counselor, I was told, “UCLA isn’t for everyone — sometimes City College is a better option for kids from schools like yours.”

This was a slap in the face. I was basically being told that I, and kids like me, weren’t capable of being successful in college, and that my more privileged peers were the ones who were meant to succeed. This injustice lit a fire in me and I leaned heavily on the lessons and values that my mom taught me; giving up was not an option and I had a responsibility to fight through this adversity and create my own success. I prioritized asking for help from my professors when I didn’t understand, reached out to my old high school teachers who mentored me and connected me to resources, and became a part of support groups with other students like me who were first-generation college students. Said plainly: I worked my tail off.

Three years later, I graduated from UCLA near the top of my class.

Being a first-generation college student from a low-income community can oftentimes feel like an impossible task, but it doesn’t have to be.

At the end of the day, all of our students deserve the opportunity to fulfill their potential without sacrificing the foundational elements that make them unique. Their cultures and experiences drive their personal values and motivations, and their challenges and adversity should be guideposts on their journeys.

Educating and preparing them for post-secondary opportunities should not and cannot ignore this — instead it should enrich them. I hope that every OneGoal student can share with pride who their families are and all of the unique elements that truly make them them. Maybe if I’d had that opportunity, I would have realized sooner that the Chhim Famous Fried Chicken wasn’t too exotic; it was perfect.